Targett

Targett

+91 33 22307241 / 42

Courtesy: THE SAGA OF INDIAN TEA by Prafull Goradia and Kalyan Sircar

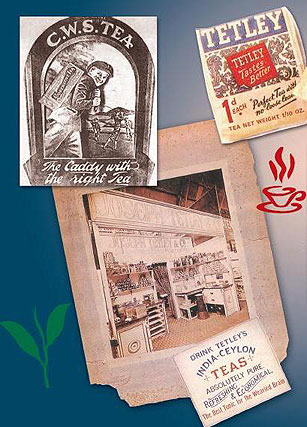

At the turn of the 20th century, the emphasis being mainly on tea production for export and the need to keep the British consumers well supplied with their teas, not much attention was paid to the internal market that was practically non-existent. It consisted mostly of special tea caddies imported into India. Liptons caddies — Green Label enjoyed a small presence.

The earliest reference to a domestic market is contained in a letter written by JRF Mackay of Brooke Bond to Arthur Brooke, who was then the Chairman of the UK Company. Equipped with capital and premises, Mackay settled down to serious business.

While it has now become the accepted management style to think in terms of objectives and strategies, it is interesting to note that even as early Mackay clearly identified his objectives:

- To pick up teas suitable for Brooke Bond blends at home, rather than getting them at Mincing Lane (London Auction Centre)

- To create and make profitable, a packet and blended tea trade in India and generally in the East.

In 1903 demand for tea as a beverage was not only non-existent but the tea habit itself was considered a vice imported by the Englishman along with cigarettes and whisky. Much of India was extremely orthodox and all foreign habits were considered alien and against Indian ethos and culture. ‘Shudh ghee' (pure clarified butter) and ‘Dhoodh Piyo’ — ‘drink more milk’ were catchwords and slogans in the Indian society. In fact, later, when tea was officially promoted by the Tea Market Expansion Board, strong religious pressure groups launched anti-tea propaganda with vigorous campaigns against tea drinking.

The domestic market was very small and hardly able to support a viable Lion. Almost all the tea consumed in the country was in packet form and nose teas came into consideration only when demand and consumption surged in the forties and fifties.

Packing material, mainly caddies and cardboard cartons, were imported the UK and the tea was floor-blended and hand-packed. An interesting of costs and a profit and loss statement is made available to us from the archives of Brooke Bond of India.

Someone called Skipworth who was in charge among other things, with his attention to the Agency business, reported the results for the year 9a4. Sales totalled around 17,000 lbs and the whole operation produced a loss ‘of 5/8 of a pence/pound without inclusion of overheads and other costs. It therefore needed a great commitment to persevere this kind of a venture.

Around the 1920s, Liptons were firmly established with their imported and Mackay, who was still in overall charge of the Indian operation, refers to the “difficulty of dislodging them from their well established onopo1y”. From this we can deduce that whatever packet tea business there was in India, was confined to the expatriate staff of the British establishments, who had their favorite Lipton Tea with imported Huntley & Palmer biscuits!

The details of distributing the tea were left in the hands of wholesalers or agents who received commissions varying from two to five percent on standard retail prices.

One such agent was Baksh Ellalue & Co., whose main business seems to have been tobacco and who had branches in Karachi, Bombay, Madras, Delhi, Rangoon and Cawnpore. They were also agents for Imperial Tobacco Co.

In the early decades of the last century, from 1900-1930, the Indian Tea Cess Committee, which later became the Tea Market Expansion Board, sold packet tea at heavily subsidised prices and remained a serious competitor to Lipton and Brooke Bond until this policy (perhaps through budget constraint( was given up in the 1930s. This made it possible for the private companies to sell their teas at more remunerative prices and also expand their sa1es.

Brooke Bond records show that they reached an average weekly sale of 1426 chests (1 chest 50 lbs) in 1930 (1.6 mkg for the year), increasing to 24,000 chests per week in the early 1960s (28 mkg per year).

Backed by the promotion and propaganda efforts of the Tea Market Expansion Board that became the Indian Tea Board through the pioneering efforts of l3rooke Bond (more about this later), a strong demand was created for tea as a beverage and the Indian masses avidly took to tea. However, much of the fallout of this phenomenon went to loose teas because of the price factor, So we see a strange development in the packet teas trade in India. In the early years, i.e. the first three decades of the century, the trade was predominantly in the hands of foreign companies and the incipient demand was centered around a small segment, introduced to tea through the Western industrial civilization. There was nothing Indian about Indian packed tea. The names were all foreign — English names. The early brand names were based on colors — Red label, Violet label, Green label.

The first sale record in India was in April 1903 and the entry reads:

Red Label ... 720 lbs

Violet Label ... 300 lbs

Green Label …180 lbs

The fact that Brooke Bond Red Label recorded 720 lbs was a very auspicious augury for this famous brand, which attained dizzy heights in later years to become the largest selling brand in the world.

All these brands were sold in quarter pound tin caddies.

The early entrepreneurs of packet tea marketing realised that if the trade had to expand, the purchase price of the tea had to be more affordable for their Indian consumer and the tea had to be better presented.

Packaging in general plays a multipurpose role in the presentation of the product.

- Gives the product a brand identity.

- Protects the product by preserving it.

- Helps to bring out the artistic and aesthetic aspects of a brand by being decorative.

In India however, the main consideration was price, one that the lower economic section of the Indians could afford. When the brands were first launched in the first decade of the century, they were priced between nine annas per lb for Red Label — the cost of the tea in the packet was roughly 60% of the total price. Despite this, prices were considered high. But the demand had been created and was snowballing — opening the floodgates to loose teas, which were at least 20% cheaper than the corresponding tea in packets.

Another problem faced by the marketing companies was dealers’ credit, It had become a very well entrenched custom and no trade was possible without extending credit. In actual fact, payment was received in a variety of ways. Small orders were sent by V.P.P. and this caused trouble when occasionally a dealer refused to take up a consignment on arrival. Certain favored dealers were allowed 30 days sight terms. Documents were passed through banks where no banking facilities were available, payment was made by hundis, (indigenous cheques).

Another novel way of payment was by divided notes. The dealer cut the Rs.l0/- or Rs.l00/- notes in half and posted the first half on one day and the second half on a later date. When both sections were received in the office it was necessary to join the halves together before submitting to the bank! This was to prevent pilferage.

Opinions on the worth and prospects of the internal business seemed gloomy. One opinion was that “Indians can never become tea-minded”. This was based on the English custom of brewing tea in pots, using a long leaf — a leisurely and luxurious habit. It is interesting to note that very early in the century, the marketers of packet tea recognised that if tea had to be made popular among Indians, it had to be presented differently, keeping in mind the Indian cooking habit of boiling. So dust tea was born. ‘Kora’ was the first brand to be introduced by Brooke Bond in paper form packets.

The real expansion of the picket business in India came in the early l920s, with the introduction of the direct selling system by Brooke Bond. As was said earlier, the distribution was left in the hands of distributors and stockiests who could do a maintenance job but could not do anything to create demand.

The depot system or direct selling system helped in introducing tea to the vast population of India but it meant a heavy investment in marketing in the earlier years. It helped in establishing a two-way communication between the salesman and retailer and cemented a personal relationship between them. For a product like tea, where freshness was an important factor, it helped in ensuring stock rotation. Under this system, the companies like Brooke Bond and Liptons, who followed suit through their own personnel, called on all retail outlets on a regular basis and supplied tea on a cash-on-delivery basis. There was no need for the retailer to carry any large inventory, as the calls were on a weekly basis.

The system backed by the effective propaganda by the Tea Board really sparked off a consumption explosion, taking India to the position of the largest tea-drinking nation in the world. Today tea has become established as a food habit in all socio-economic sections.